The former striker opens up to Sports-Prediction: “I was an introverted boy, no one helped me, the pitch was my only refuge. In Manchester, I earned respect with a tough attitude.”

Tears, suffering, falls and comebacks, sporting and family dramas overcome in the name of extreme, extraordinary resilience. Pepito Rossi’s story is well known. A series of injuries, years of football lost, including two World Cups denied him in painful circumstances, a life marked by deep wounds. “And don’t make me tell you about it for the umpteenth time, I don’t want to go to therapy, everyone knows about it and it makes me feel anxious…” he says from New Jersey, where he is coaching the boys at his Campus. OK.

So, since you’re surrounded by children, let’s go back to the summer of 1999, when you arrived in Parma from the US. You were 12 years old. What was your relationship with Italy like?

“Wonderful. Every summer we would leave Clifton, New Jersey, and spend a month and a half in Italy. We stayed in Fraine, a village of 500 souls where my father was born, in the province of Chieti. And then Acquaviva di Isernia, Molise, another small village where my mother came from, and the sea at Vasto.“

How did your parents meet?

”At school, in Clifton, where they both taught. My father arrived in America when he was 16, my mother when she was 13.“

Fraine, you said.

”It felt like New York to me. I lived in a typical American TV show row house and could only get around by car. There was no sense of community, it was a very closed life at home, and none of the neighborhood kids wanted to play soccer. They only thought about basketball, football, and baseball, and I played two-on-two with my father, mother, and sister. There was this concrete field in Fraine where we spent our days playing endless games, and then in the evening we went to the square for soccer and music. It was absolute freedom. We roamed around undisturbed, carefree, with no worries. I felt like I was 30 years old.“

How did you end up in Parma?

”At one point during the vacation, my father took me to Tabiano Terme for a week to a summer soccer school. I went there for three years and a Parma scout saw me there.”

Tough decision.

“Terrible. Deep down, I didn’t want to go, but I didn’t want to disappoint my dad. So he and I moved to Salsomaggiore, and my mom and Tina, my sister, stayed in Clifton. It was really tough: at home we spoke 40% Italian and 60% English, and I struggled terribly with writing, as well as French and math, which is much more advanced in Italy than in America. I was a shy, introverted kid, I had trouble making friends, and the teachers thought I was only there for soccer and didn’t help me at all. And then there was the homesickness. I cried every single night until my mom came to visit us: a month and a half had passed, but it felt like three years. I was only happy on the field. That was my refuge, the only place where I could breathe and feel comfortable.”

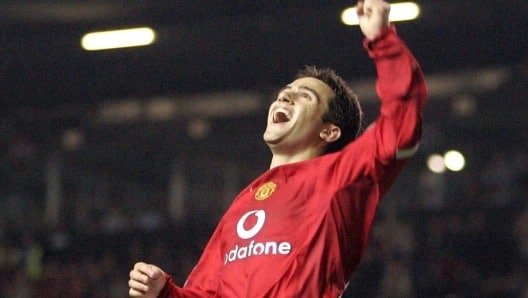

And to complicate his life even further, at 17 he ended up at Sir Alex Ferguson’s United.

“They had a scout in the area, and one day in May 2004, he approached me, gave me a Manchester United pin and told me they wanted me. I thought it was a joke, I gave the number to my dad and it was all true. It was a very important four-year contract and the chance to train with the first team of what was then the most important club in Europe.”

Your first meeting with Sir Alex?

“At the signing. It was a surprise: an austere but affectionate and attentive person, close, a father figure used to treating young people like jewels, protecting them and encouraging them to grow as people and as footballers, with very precise and clearly defined values and rules. We got along because I had great ambition and a good upbringing. My father had raised me very strictly in this regard; if I stepped out of line, he would immediately put me back on track.”

And in training?

“Incredible. Another planet. A different sport compared to what I was used to. Beastly speed and brutal intensity. You know the famous saying, ‘You play as you train’? Well, my father always repeated that to me, and at United it was like that, but multiplied by a thousand. There were no friends in training: just kicks, shoves, aggression.“

And how did you react as a 17-year-old striker?

”I quickly realized what I had to do. I had talent, I had to use it to earn the respect and trust of those monsters. Physically, I was behind, I had to get by with technique and intelligence.”

And then?

“I had to think at a new speed. Before the ball arrived, I had to know what to do with it. Otherwise, Gary Neville or Nemanja Vidic would be there to wake me up. Some of the beatings… There’s an anecdote that perfectly captures my state of mind at the time. Roy Keane recounted in his autobiography that once in training he had told off a young Italian player for not passing him the ball, and the boy responded with a hard, defiant look. ‘If he had said anything to me, I would have hit him. He kept quiet, but his look was clear, he was telling me to get lost. I thought about going over to shake his hand,’ he wrote. That boy was me. And I don’t remember the episode at all: I was obviously in competitive trance, in training! My determination to make a career was absolute.“

When you arrived in Parma, did you ever think about giving up and saying to your dad, ‘Let’s go home’?

”Yes, many times. But I never told him, or my mother, or anyone. I didn’t want to disappoint him, but above all, I didn’t want to lose, and I wanted to be the one to have the last word. It was the same with injuries later in my life: I always came back. I would be the one to decide when to give up, not a doctor or a manager, and that’s how it went: I played my last five games with Spal and then I stopped.”

“Difficulties help, they are necessary in a process of growth and learning. I was lucky to have to face them at such a young age, with my father’s help. When he passed away in 2010, when I was 23, I was ready. He had prepared me for life and therefore for what I would go through afterwards. The suffering of Pepito as a teenager was fundamental in helping Pepito as a man overcome the great difficulties he encountered along the way.”